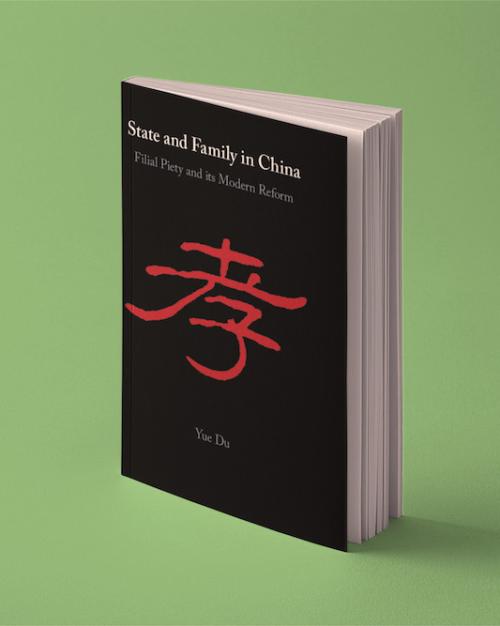

In Qing Dynasty China (1644-1911), laws favored parents over children – for a political purpose, according to Mara Yue Du, assistant professor of history in the College of Arts and Sciences. Take the case of Wang Dacai, which opens her book “State and Family in China: Filial Piety and its Modern Reform.”

In 1815, a son’s slight injury to his father was deemed a “violation of fundamental human ethics.” The child was arrested and faced death or exile. The father, named Wang Dacai, committed suicide upon hearing of the severity of his son’s punishment.

“This case may seem ridiculous in modern eyes. But it speaks to how Qing filial piety law worked: Parents can never be wrong, at least for their children,” said Du, whose research centers on the history of modern China. “And it reveals that Qing law’s upholding of parents’ authority was not only about maintaining household heads’ control over their families, as many scholars believe, but to enforce a relational power parents enjoyed over their offspring, which was then analogized to officials’ and the emperor’s authority over commoners.”

Chinese legal institutions in different eras upheld or undermine parental authority over children to serve political goals, Du argues in her book: ruling the empire effectively at a low cost during the Qing, and separating individuals from families to subjugate them directly to the state in the 20th century.

And the state’s instrumentation of family relations for purposes of governance are not all in the past Du said; during recent trips to China, she’s observed that President Xi Jinping promotes his “China Dream” through media and street posters celebrating filial piety and other “traditional Chinese values,” calling for citizens’ obedience to authorities and devotion to the state.

“Culturally and politically, the past is not even past,” Du said.

Du will talk about “State and Family in China” on April 13 at 4 p.m. in Olin Library 107 (with a virtual option).

The College of Arts and Sciences spoke with Du about the book.

Question: You write that your book is ‘a national history with local perspectives.’ Where did you find these?

Most of the cases I discuss in the book are from local archives.

What is interesting for me is that despite variations in local legal cultures in such a big country, cases involving inter-generational conflicts were handled rather similarly by local legal authorities across the empire, resulting in a similar entitlement parents felt over their adult and minor children, and a similar trepidation children felt toward parents and their understanding about the state’s support of parental power. When the state tried to weaken parental power and atomize citizens in the 20th century by reforming the law, new laws were again enforced relatively uniformly nationwide.

Question: Looking at the way various regimes view and use parent-child relationships, how has China changed in the past two centuries? And what has remained the same?

On the one hand, younger generations in the 20th century used new, more “progressive” laws to undermine parental control over their property, marriage, place of residence, etc., leading to the gradual decline of the parent-child hierarchy. On the other hand, the driving force of “dismantling the family” was not to free individuals, but to serve the state. Young people’s victory over parental power contributed to more stringent control the state had over individuals.

During the Maoist era, children were called upon to educate their parents, whose minds had been corrupted by “feudalism,” and children were even encouraged to disown parents if they found their parents were disloyal to the state. As the state’s anti-family campaigns went to such an extreme during a period of social chaos and economic scarcity during the 1960s and the 1970s, the underlying tide started to turn in society, opening the door for the revival of family values, including filial piety, since the 1980s.

Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party are trying to ride this tide in recent years, advocating for filial piety as a way to oblige children to support their elders in absence of an equitable welfare system in China. And it tries to strengthen the logic of “filial obedience,” which is the word for filial piety in the Chinese language, and to direct such obedience toward the state. Without filial piety law to support such propaganda and moral educational campaigns, I doubt how successful this state-sponsored revival of traditional value would be in serving the regime. But the intent of the state is obvious.

Question: The book describes cases of parents and their children set against each other in legal cases and/or by state manipulation. Did you come across any cases of families defying state attempts to pit family members against each other?

During the Cultural Revolution (1967-1977), most children, despite state propaganda, did not denounce their parents and treat Mao as dearer than their parents. They understood that their parents, and their family, were the last harbor they had in the stormy sea. Most people in China might simply love their children and their parents, even when they were living under such stringent filial piety law in imperial China or in society that was filled with anti-filial piety discourse in the 20th century.