Governments and businesses should strive to limit the use of economic sanctions, which have increased dramatically since the 1970s, advises Nicholas Mulder, assistant professor of history in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Sanctions are “pushing globalization in a more unstable and military conflict-prone direction,” Mulder wrote on the World Economic Forum’s Strategic Intelligence website, and “the most effective sanctions are often those that are merely threatened.”

The forum tapped Mulder to share his expertise on sanctions and other key trends in geo-economics for Strategic Intelligence, which seeks to help government, private sector and nonprofit constituents make sense of the forces driving transformational change in the global economy.

“There’s a lot of talk about a crisis of globalization,” Mulder said. “Practitioners and policymakers are looking for historical perspective to understand and anticipate what might happen.”

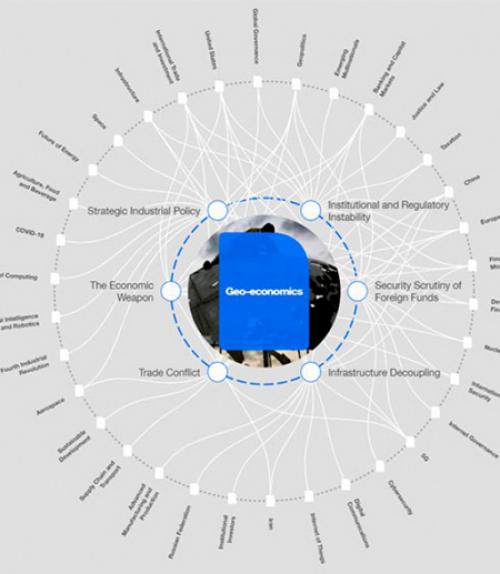

Mulder contributed essays on six trends in geo-economics, which refers to nation-states trying to achieve strategic aims through economic means. Mulder calls sanctions “the economic weapon,” which is also the title of his forthcoming book. The other trends he addressed are trade conflict; institutional and regulatory instability; security scrutiny of foreign funds; infrastructure decoupling; and strategic industrial policy.

Mulder curates a feed of recent news and research on the Strategic Intelligence site, which also features a “transformation map” that visualizes how each geo-economics trend intersects with other subject areas. Sanctions, for example, link to nine topics including financial and monetary systems, international security and Iran.

“The map provides an important resource for users seeking to understand and position themselves in the modern global economy,” said James Landale, head of content and partnerships for Strategic Intelligence, a publicly available site with more than 250,000 users.

Mulder said the platform offers an opportunity to step back from the tumult of the daily news cycle to consider a bigger-picture context for the financial crises, rising nationalism and trade wars that have placed international institutions under pressure over the past decade.

“There’s a broad perception that this is a historic moment, and there’s a need for this kind of analysis,” he said. “History provides a rich and sophisticated way of understanding some of these shocks and developments.”

Geo-economics as a term dates to 1990, and geo-economic rivalries did not fully emerge until after the 2008 financial crisis, Mulder wrote on the site.

But his analysis draws on expertise in the interwar period – from November 1918 to September 1939 – which many see as providing a parallel to the present, Mulder said. The comparison has prompted fears of impending “de-globalization,” a term Mulder said he considers misleading.

“It’s not de-globalization but globalization moving in a different direction from what we have become used to,” he said. “What we’re seeing is not the world falling apart, but certain connections that existed before are decreasing and connections in other areas are increasing.”

On a hopeful note, Mulder, who this fall plans to teach a course titled, “Stability and Crisis: Capitalism and Democracy, 1870 to the Present,” said recent global events don’t presage a rerun of World War II. On the other hand, climate change represents a severe new stress that will require an unprecedented and urgent level of cooperation between nations.

“Global stakeholders should think about how to best contain geo-economic tensions,” Mulder wrote. “Concerted public-private action, for example, could help revive effective international cooperation on matters like climate change, migration and the impacts of COVID-19.”