This is an episode from the “What Makes Us Human?” podcast's fourth season, "What Does Water Mean for Us Humans?" from Cornell University’s College of Arts & Sciences, showcasing the newest thinking from across the disciplines about the relationship between humans and love. Featuring audio essays written and recorded by Cornell faculty, the series releases a new episode each Tuesday through the spring semester.

I would describe myself as a historian of water. I look at the ways that water, open ocean, regional seas, and even rivers and creeks have connected disparate geographies. It’s an irony to me that I ended up in Ithaca, a place that is land-locked; but that makes me pine for water even more.

My geographical focus is Southeast Asia, home to the world’s largest archipelago, Indonesia. The countries that now make up Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, and the southern parts of Thailand and the Philippines have borders that were primarily drawn across open seas. Water separates, but it also connects, and many ethnic groups which had always moved across the seas of Southeast Asia are now separated by imaginary lines on maps. Smuggling has been one response to such borders. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, smugglers made their way around these seas trying to trade outside the vision and reach of advancing European colonial states.

Water plays a central role in the history of the pilgrimage to Mecca from Southeast Asia. Around the turn of the 20th century, around half of all global pilgrims to Mecca came from Southeast Asia, despite the fact that it was the part of the Muslim world that was furthest away.

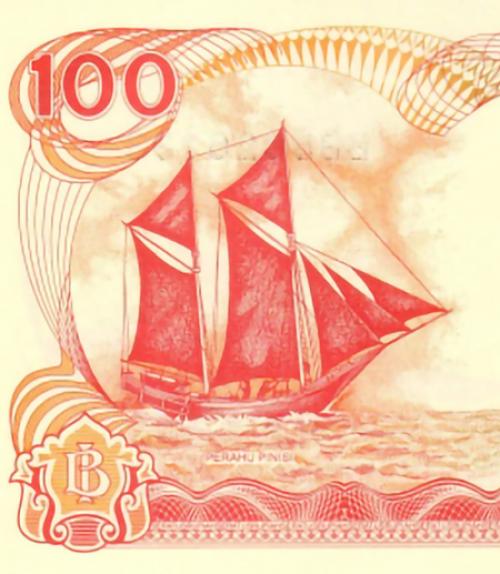

For centuries, sailing ships hugged the coasts of Asia in making this journey. They had to rely on the monsoons, the winds and currents that allowed humans to travel with the natural rhythms of the planet.

This changed in the mid-19th century, when steamships started to make these trips possible at any time of the year – but, ironically, the ships were owned by Europeans, the burgeoning colonial masters of the region. Western colonial regimes wanted the profits of ferrying their Muslim subjects across the Indian Ocean, but they were very wary of the resistance ideologies that they brought back with them.

There’s lots more to know about how the sea connects the various societies that stretch across Asia, the largest of the world’s continents, reaching from Turkey all the way to Japan. These places were linked in an increasingly intense embrace – economically, culturally, politically – over the past 500 years, all via the patterns of shipping on the sea. Long-distance exploration brought this huge maritime space into a single, inter-connected web.

One good example: when a giraffe was brought back from Africa by a Chinese explorer in the early fifteenth century and paraded across the Chinese capital, no one quite knew what they were looking at. Everyday Chinese though it was a “qilin”, a mythical beast. Only the sea, and the conquest of the sea through knowledge and advancing technologies of seamanship, made this new knowledge of the world and its many creatures possible.

I’ll be looking at these patterns further in a class called “The History of Exploration,” which I’ll be co-teaching with Cornell astronomer Steve Squyres. Steve’s been running Mars rovers for NASA; he’ll deal with exploration in the heavens, and I’ll stay down on the terrestrial globe. So I’ll still be making my way by sea, even as I sit landlocked here at Cornell, looking out over the rolling green hills of Ithaca.

Image: Traditional Indonesian two-masted sailing ship featured in 100-rupiah banknote.